Mar 19, 2010 0

Vincere [Marco Bellochio, 2009]

Vincere means victory, and Bellochio’s latest is a win from start to finish. I saw this film last year at the New York Film Festival and was blown away — almost literally by the Italian Futurist supertitles that whoosh in from above and nosedive their way onto the screen. The film paints a thrilling historical portrait of Ida Dalser, Il Duce’s first wife and suppressed love interest who bore him a child. Aside from its stunning visuals, the film is enlivened by an absolutely bravura performance by Giovanna Mezzogiorno, who is widely known in Italy, and should be more well-known here. An opening shot/reverse shot sequence reveals her attraction for Mussolini as she watches him denounce God in his characteristically overbearing oratory.

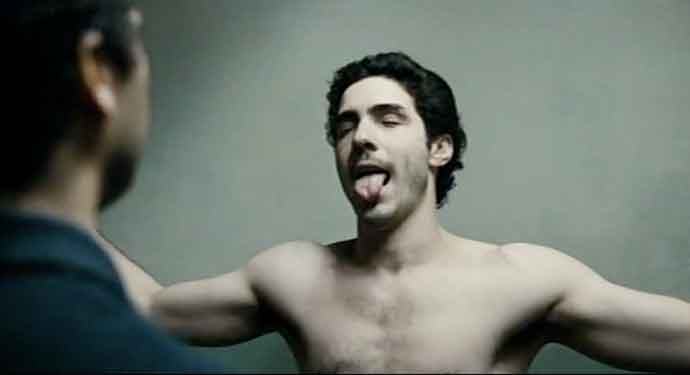

A young Mussolini [Filippo Timi] addresses the crowd.

Giovanna Mezzogiorno as Ida Dalser is aroused by his singular vision.

She is among the many who fall under his rhetorical spell.

This sequence makes it pretty clear that the qualities that make her lust after Mussolini are the same that compel the Italian people to fall for fascism, and that we are to read Dalser’s seduction and subsequent betrayal by Mussolini as allegorical. While it’s entirely possible to read this movie as *only* a historical portrait, you’d be missing half the fun, because Vincere is among the most biting satire that Bellochio has ever produced. The sheer pompousness of some the newsreel footage, the grandiose media gestures and spectacles — Bellochio ushers them in like gangbusters in this condemnation of the state. And yes, Il Duce is an easy target (perhaps too easy) but that doesn’t mean Vincere isn’t worth applauding. Bellochio’s arrows never lack sting, especially in light of contemporary media fascists like Berlusconi.

And for those who love the aesthetics (er, not the politics!) of Italian Futurism, the film offers of a visual feast of fashion, fonts (including the aforementioned supertitles above), and historical footage.

An Italian Futurist Study Guide (To brush up before you go).

Or you can just take a cue from F.T. Marinetti:

“We will glorify war — the world’s only hygiene — militarism, patriotism, the destructive gesture of freedom-bringers, beautiful ideas worth dying for, and scorn for woman. We will destroy the museums, libraries, academies of every kind, will fight moralism, feminism, every opportunistic or utilitarian cowardice.” –The Futurist Manifesto