Nov 8, 2011 1

Contempt (Moravia first, then Godard)

On a friend’s recommendation, I just finished reading Alberto Moravia’s Contempt, which was adapted by Godard for his eponymous film. Moravia’s novels have served as fertile source material for several iconic European auteurs, including Bertolucci (The Conformist), and Vittorio de Sica (Two Women). A new edition of Contempt was published by the NYRB Classics imprint in 2004, along with Moravia’s Boredom. English translations of these novels had been out of print for close to 50 years, so their re-introduction heralded something of a mini-Moravia renaissance.

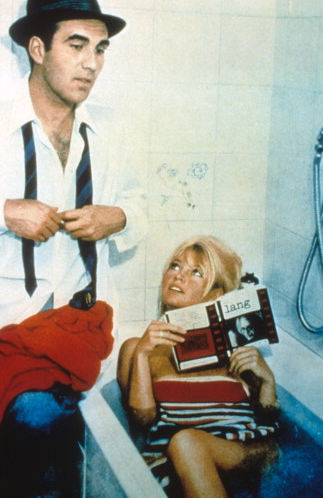

Known for his rendering of modern psychological states, Moravia’s novels are rife with cultural references, such as German opera and Greek tragedy. However, while Godard shares this proclivity towards reference, he abandons Moravia’s first-person narrative in favor of numerous meta-narratives, alienation over traditional identification with characters, and an all-over Brechtian estrangement of the audience. Godard keeps the basic framework of the plot intact, yet manages to produce a film that feels wholly alien to Moravia’s sensibility. For more on the distance between the two “Contempts,†there’s a lovely essay by Anne Carson that looks at both texts though the eyes of a classicist. But for me, the formal rigor of Godard’s film far surpasses the artfulness of Moravia’s writing—a judgement I concede is completely unfair since I read Moravia in translation. But to each her own.

Godard’s comments on the novel are less than charitable — perhaps he resented remaking a bestseller, regarding the text as yet another ugly manifestation of the highly commercial production. Regardless, his notes on the adaptation are uncharacteristically direct, revealing his intentions like an overhead light illuminating the corners of the room.

Godard on Le Mépris

Moravia’s novel, Contempt, is a nice, vulgar one for a train journey, full of classical old-fashioned sentiment in spite of the modernity of the situations. But it is with this kind of novel the one can often make the best films. I have stuck to the main theme, simply altering a few details on the principle that something filmed is automatically different from something written, and therefore original. There was no need to try to make it different, to adapt it to the screen All I had to do was film it as it is: just film what was written, apart from a few details, for if the cinema were not first foremost film, it wouldn’t exist. Mélies is the greatest, but without Lumière he would have languished in obscurity.

Apart from a few details. For instance, the transformation of the hero who in passing from book to screen, moves from false adventure to real, from Antonioni inertia to Laramiesque dignity. For instance also the nationality of the characters: Brigitte Bardot is not longer called Emilia but Camille, and as you will see she trifles none the less with Musset. Each of the characters, moreover, speaks his own language which, as in The Quiet American, contributes to the feeling of people lost in a strange country. Here, though, two days only: an afternoon in Rome, a morning in Capri. Rome is the modern world, the West; Capri, the ancient world, nature before civilization and its neuroses. Le Mépris, in other words, might have been called In Search of Homer, but it means lost time trying to discover the language of Proust beneath that of Moravia, and anyway that isn’t the point.

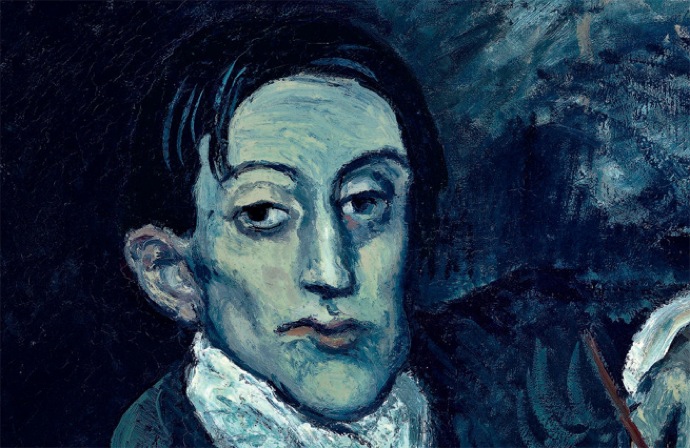

“The point of Le Mépris is that these are people who look at each other and judge each other, and then are in turn looked at and judged by the cinema–represented by Fritz Lang, who plays himself, or in effect the conscience of the film, its honesty. (I filmed the scenes of The Odyssey which he was supposed to be directing in Le Mépris, but as I play the role of his assistant, Lang will say that these are scenes made by his second unit.)

“When I think about it, Le Mépris seems to me, beyond its psychological study of a woman who despise her husband, the story of castaways of the Western world, survivors of the shipwreck of modernity who, like the heroes of Verne and Stevenson, one day read a mysterious deserted island, whose mystery is the inexorable lack of mystery, of truth that is to say. Whereas the Odyssey of Ulysses was a physical phenomenon, I filmed a spiritual odyssey; the eye of the camera watching these characters in search of Homer replaces that of the gods watching over Ulysses and his companions.

A simple film without mystery, an Aristotelian film, stripped of appearances, Le Mépris proves in 149 shots that in the cinema as in life there is no secret, nothing to elucidate, merely the need to live—and to make films.

P.S. Another advantage that the film has over the book is the score—which I unconditionally love. You can download the iconic theme music here: 16 Le Mépris-Theme De Camille.