Oct 28, 2011 1

Chroma [Derek Jarman, 1994]

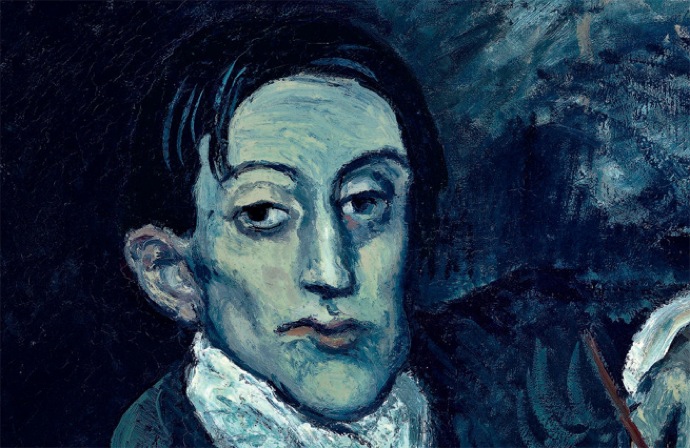

I have been thinking a lot about color, and about artists and their relationships to their materials. I myself am a color junkie, and dramatic color is like a shot of adrenaline to me. The directors/cinematographers who share my chromophilia — Vincente Minnelli, Antonioni, Almodóvar, and Zach Cardiff’s cinematography in The Red Shoes immediately come to mind — understand the emotional essence of each shade in the spectrum. Red excites and stimulates. Green is a sedative. Yellow vacillates between sunny and sickening. Orange is talkative. Blue is always one of two moods: Yves Klein Electric or Plaintive Picasso.

Lately I have been struck by the fact that the intensity of a certain hue is umbilically tied to its medium. Technicolor is indisputably the most significant development for color filmmaking in the 20th century, and one could argue that it precipitated a completely new approach to directing — new lighting, new make-up, even a new kind of acting. This is in stark contrast to digital filmmaking in which the majority of color correction happens in the post-production phase. Since the advent of digital, there has been a definite trend towards over-saturated colors that I would like to see go away, or at least toned down to avoid actors looking like Oompa-Loompas (then again, maybe they tan too much).

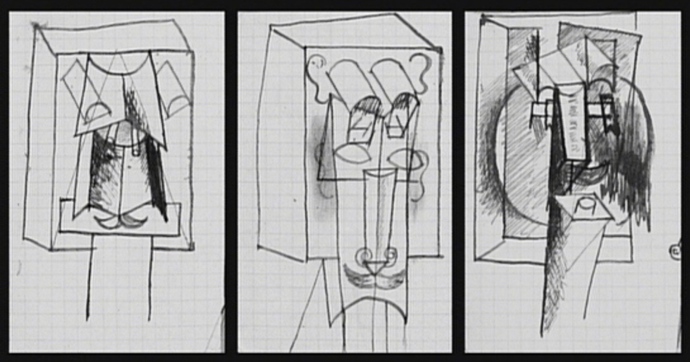

But where does color come from? A filmmaker would think about color in terms of light or projection, but a painter would instantly think about paint and pigment. This understanding of color is first and foremost practical — pigments are not abstract, but material substances with chemical attributes. Paint has a particular consistency and texture. If you run out, you can’t complete your painting.

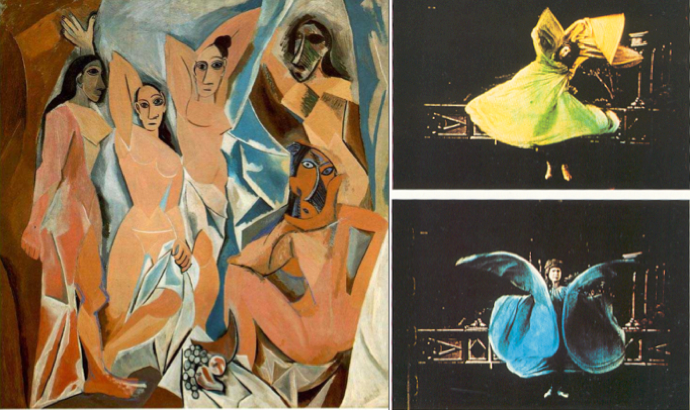

Derek Jarman’s book Chroma explores both the material and the spiritual implications of color, from the perspective on an artist who has worked in both painting and film. Written while Jarman was losing his eyesight due to complications from AIDS, it is an elegiac meditation on what colors signify, and how they exist in the real world. There are 19 vignettes in total, some named after different colors, along with essays on perspective, shadow and light, translucence, and iridescence.

I find it fascinating to read Chroma against the backdrop of Jarman’s films, which run the gamut from grainy 8mm shorts to 35mm Technicolor features. Here are some excerpts juxtaposed against film stills that showcase Jarman’s innate feel for color, both as light and pigment.

May my black Waterman ink spill out the truth.

Chemistry and romantic names — manganese violet, cerulean, ultramarine and distant places, Naples yellow. The geography of colour, Antwerp blue, raw Sienna. Colour stretching to the distant planets — mars violet; named after old masters — Van dyke brown. Contradictory — Lamp black.

1919. The world is in mourning. Kasimir Malevich paints White on White. A funeral rite for painting.

When yellow wishes to ingratiate it becomes gold.

Red is a moment in time. Blue constant. Red is quickly spent. An explosion of intensity. It burns itself. Disappears like fiery sparks into the gathering shadow.

Wasn’t Dorian Grey’s brain speckled with the scarlet stain of insanity?

Painters use red like spice.

Pink is always shocking. Naked. All those acres of flesh that cover the ceilings of the Renaissance. Pontormo is the pinkest painter.

I’m dreaming of a white Christmas. This song could only be sung in Southern California around a swimming pool.

Leni’s full moon falling through a crystal grotto in the High Dolomites

Blue movies

Blue language

Bluebeard

The most stable of greens is the Terre Vert. The most elusive, the copper greens that turned all the Venetian paintings brown. Fugitive colour flies in time, and leaves us in a perpetual autumn.

How Now Brown Cow

There is nostalgia in brown. The touch of my mother’s soft beaver lamb coat in which we buried our tears. Brown simplified life.

Who has not gazed in wonder at the snaky shimmer of petrol patterns on a puddle, thrown a stone into them and watched the colors emerge out of the ripples…

Where did glass appear in my films? Faces distorted, pressed into the window.

And then there is Jarman’s Blue. Filmed in Technicolor, this cine-poem is both plaintive and electric, and is perhaps the saddest movie I have ever seen. It speaks for itself: