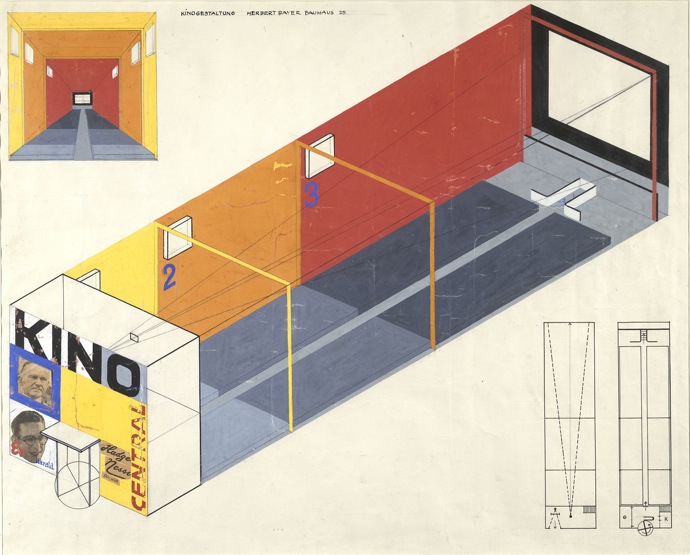

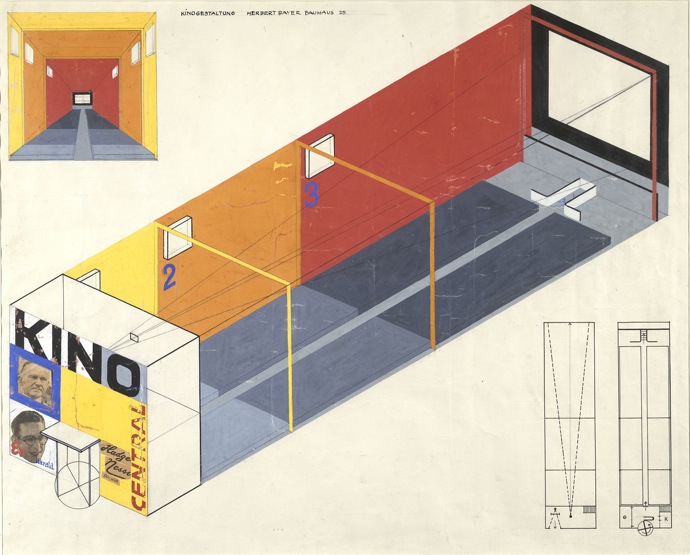

This weekend is your last chance to catch MOMA’s Bauhaus exhibit, which is enlightening because it reveals that its practitioners (check out those cool cats below) were far from uniform in their approach to art, architecture and life. For me, the big discovery was Herbert Bayer’s design for a cinema [1924-25] and what he calls a “multimedia” trade fair stand to be used for advertising purposes [1924].

In da Bauhaus (actually they were on the roof. Herbert Bayer is fifth from the left.)

Bayer’s design for a cinema is notable for what it lacks: it dispenses with a marquee, which was designed to “embrace” the potential moviegoer on the street and funnel him into the theater. The revolving door is more characteristic of a department store. And I have no idea what those three primary colored zones are meant to indicate. But one can immediately see that this cinematheque is the exact opposite of the movie palaces of the 1920’s, which were derived from theater architecture and were intended to create an opulent and exotic experience.

Even more radical is this multimedia kiosk for a fictional brand of toothpaste, “Regina.” Presumably the booth would lure you in with the sound of her voice.

Bayer is most well known as a type designer. He was a proponent of the almost ubiquitous use of all lowercase letters, and he created the quintessential Bauhaus font Universal, which still looks fresh today. But he also wrote presciently about exhibition design in a way that anticipates future developments in digital media:

“Exhibition design has evolved as a new discipline, as an apex of all media and

powers of communication and of collective efforts and effects. The combined

means of visual communication constitutes a remarkable complexity: language

as visible printing or as sound, pictures as symbols, paintings, and photographs,

sculptural media, materials and surfaces, color, light, movement (of the display

as well as the visitor), films, diagrams, and charts. The total application of all

plastic and psychological means (more than anything else) makes exhibition

design an intensified and new language.”

Here, film is subsumed under a multimedia gesamtkunstwerk that attempts to alter all aspects of the user’s experience. It was already considered just one tool in the virtual reality shed as early as the 1920’s.