Jun 30, 2011 0

Marilyn Monroe: Actress, Icon, ______

Marilyn Monroe was known for two things above all: a dazzling smile and a tremor in her voice. On the screen, those features were shaped into a surprisingly varied cast of characters. The Marilyn who knocked everybody out cold in Some Like it Hot is different from the Marilyn who almost stole Monkey Business right out from under Ginger Rogers’ nose. And the show-stopping Marilyn who proved, once and for all, that Gentlemen Prefer Blondes is yet another Marilyn, a four-alarm fire practically burning a hole through the screen in Niagara.

She had considerable dramatic range as an actress, and a well-honed sense of comedic timing. As Montgomery Clift’s character Perce Howland mulls in The Misfits, “She’s kinda hard to figure out, you know? One minute she looks kinda dumb and brand-new, like a kid… and the next minute…†Her character, as well as the actress herself, remains an enigma, to be showcased in BAMcinématek’s series, Marilyn!, from July 1 to 17.

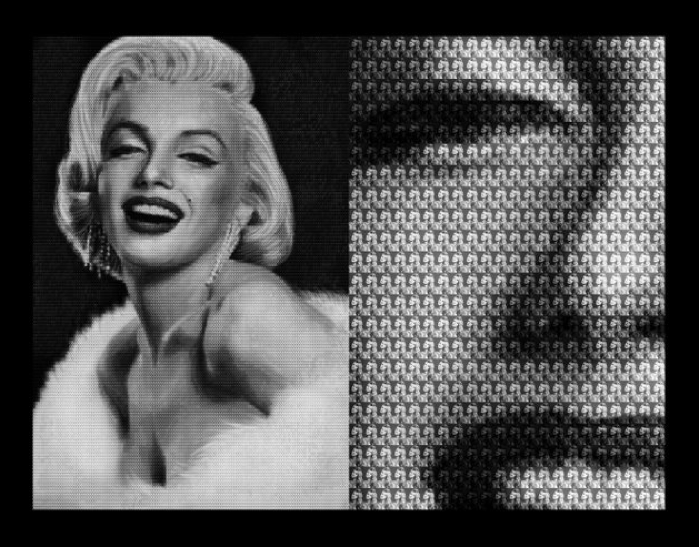

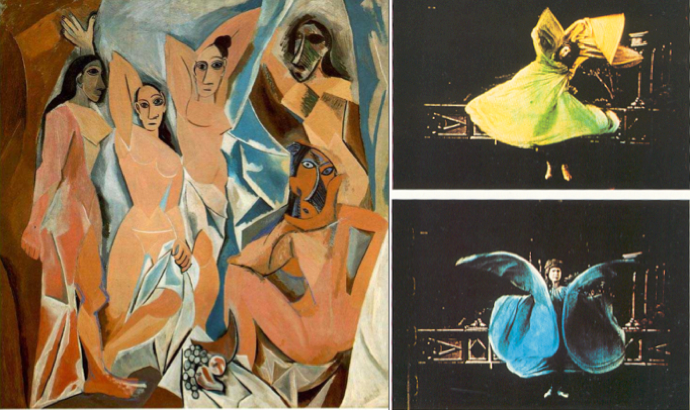

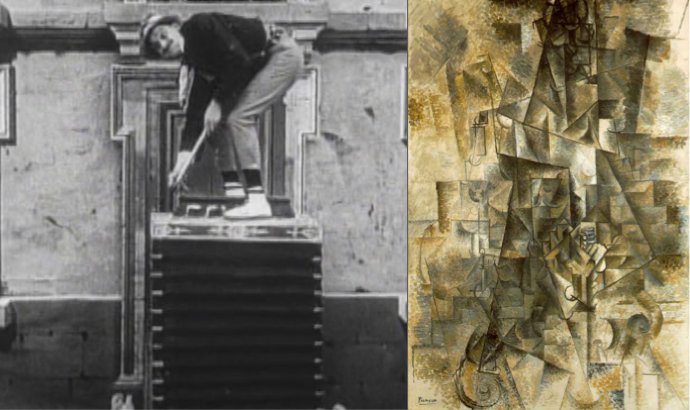

But first, let us consider Marilyn’s mythic projection, or Monroe the icon. This Marilyn is indelibly written into our consciousness as the golden, open-faced beauty, epitomizing a healthy American sexuality and a vulnerable, childlike innocence. Here, all the nuance of her myriad characterizations is lost, and she becomes a series of frozen images. This is the Marilyn from The Seven Year Itch who felt the gust of air from the subway grate, immortalized with her dress blooming around her like a flower. This is Andy Warhol’s silkscreened Marilyn, her celebrity reduced to her mug in a rainbow of colors reproduced ad infinitum. This is Marilyn in the realm of high camp, draped in diamonds and surrounded by ostrich plumes, cooing “Diamonds Are a Girl’s Best Friend.†There are abundant variations on this theme but the girl at the center remains the same: an erotic fantasy, an imaginary creature that can only exist in the cinema.

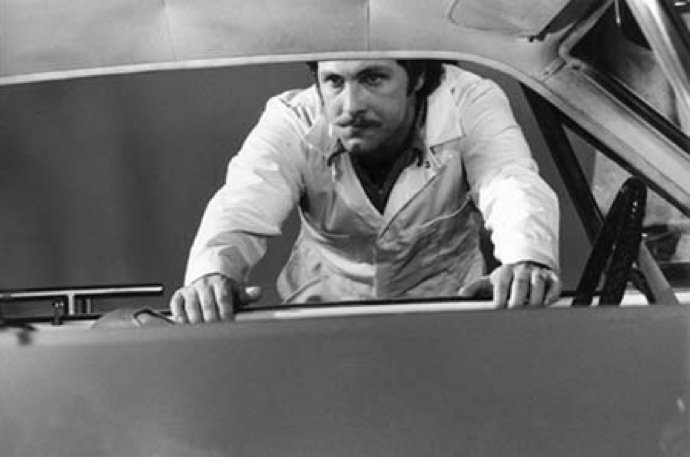

Monroe’s beginnings were far from auspicious. The woman who was to become a universally known and loved icon of the 20th century was born Norma Jeane Mortenson in Hollywood. Her mother was a film cutter at RKO Studios who, widowed and mentally ill, abandoned her to a sequence of foster homes. Monroe’s childhood was marked by crippling poverty and abuse, and she married at 16. It was then that she started to achieve some success as a model and was scouted by Howard Hughes, then the head of RKO Studios. He offered her a screen test but she ended up signing with 20th Century Fox. Her first major break as an actor was in John Huston’s gritty LA film noir, The Asphalt Jungle, in which she played a memorable mistress that lit up each of her scenes. She won another small but significant role in Joseph Mankiewicz’s All About Eve, in which she held her own among a formidable cast that included Bette Davis and Anne Baxter. Mankiewicz predicted her rise to fame, claiming that she had that certain indescribable something, that ineffable star quality. Watching All About Eve, it is evident that Marilyn knew she had it too.

But she wanted to play more than arm candy. In addition to roles for which Monroe is celebrated, the BAMcinématek series includes some underrated gems that never achieved box-office success but nevertheless remain crucial landmarks in her development as an actress. The first of these is Don’t Bother to Knock, her first serious role in which she plays a mentally unhinged babysitter. She’s unstable and creepy, and it’s thrilling to watch her face morph from hardened to sweet to insecure in an instant. Still another role in which she expands her repertoire is opposite Robert Mitchum in the thrilling action epic River of No Return, shot in lush CinemaScope. But if you see just one film from this series, let it be John Huston’s twilight Western, The Misfits, penned especially for her by her then-husband, playwright Arthur Miller. Film critic Pauline Kael wrote of Marilyn dismissively, proclaiming “When she was ‘sensitive’ she was drab,†but Monroe has never been more sensitive than in The Misfits, and has never looked more radiant. Miller wrote this role particularly with Monroe’s dramatic strengths and biography in mind, and it’s astounding to watch. It’s also the last film that she completed.

Shy, bright, sensitive, and unaffected, Monroe hated being a star. She was the woman most fantasized about by men (a fact that embarrassed her), yet fame became a painful thorn. It’s an old story, but still a sad one, and whatever factors contributed to her untimely death, one thing is certain: Marilyn was made for the medium of film.